Introduction

Climate change needs an equitable solution. Historically, human development across the world has been uneven. Until 2022, developing and emerging countries still house a large share of extremely poor individuals. Improvement of socioeconomic well-being through development is needed in these countries. Climate change, which inflicts damage and disrupts livelihoods, raises the risk of entrenching global inequities, making development more challenging. However, policies ostensibly dedicated to addressing climate change can themselves engender new inequities that adversely impact some groups and benefit others.

Global climate-resilient development, therefore, entails a global collaborative effort that is fair towards subjects with different levels of responsibility and capability. National climate policies also need to consider equity, both in terms of the national contribution to a global effort and intra-national redistribution of costs and benefits.

Climate change as a distributive problem

Climate change is a problem with many dimensions. At the physical level, a polluted atmosphere leads to global warming, whereby excessive heat is stored in the climate system, amplifying climate extremes. Consequently, we are pushing hard on the upper limit of the planetary boundary conducive to life on Earth. At the societal level, humanity faces significant risks of unmanageable damage from cascading climate impacts. This is problematic when our socioeconomic system heavily relies on the use of fossil fuels, which is the main source of greenhouse gas (GHG) pollution.

The material exchanges and flows within the global economic system, powered mostly by fossil fuels, have driven both socioeconomic development and climate change. However, the global economic system that produces material wealth of such scale has done poorly in equitably distributing the benefits it has generated.

Human well-being, in terms of life expectancy, health, education, and poverty, has improved unevenly worldwide over the past two decades. In many least-developed countries, basic living standards are far from being met, whereas developed countries enjoy material wealth that is not well deployed to uplift the welfare of those in need. For example, the agreed target of official development assistance (ODA) is 0.7% of gross national income (GNI), but the size of the delivered ODA stood at 0.36% of development assistance committee (DAC) countries’ GNI in 2022. In developing countries, climate change threatens impacts that thwart development progress, which is needed to alleviate sub-national inequities, while the urgent need to mitigate global warming constrains developing countries’ options.

There is a need to anchor climate change policymaking on an equity principle. As enshrined in international treaties such as the United Nations Framework Convention for Climate Change and its corollary protocols and agreements, any global pursuit to solve climate change should be made on the principle of equity and “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities” (CBDR-RC). CBDR-RC endorses “asymmetrical commitments of different states to ensure universal participation and effective implementation.” This means that country parties are held to different levels of obligation in mitigating climate change according to their respective responsibilities in causing the problem and respective capabilities in solving the problem.

The CBDR-RC principle guides countries to divide appropriate burdens for addressing climate change among themselves. What is an equitable way of distributing the burdens of addressing climate change?

What do we mean by climate equity?

Many climate solutions proposed now are market-based, such as carbon pricing, emissions trading schemes, and voluntary carbon markets. According to the view of the market-based approach, carbon is an externality that is not correctly priced to represent its damage to society. Market instruments allow carbon emissions to be valued to impute the cost of carbon pollution, and like commodities, their abatement cost can be traded in the market to achieve cost efficiency. This idea is based on the principle of Pareto efficiency, which states that the benefit (cost) of one’s emission (abatement) should not come at the expense of the cost (benefit) of another.

This principle is problematic, for it does not consider history. The current benefit that developed countries enjoy came as the result of the deep damage inflicted by imperialism and industrialisation on the colonised countries. Past emissions also have effects on current climate impacts, as GHGs accumulated in the atmosphere raises global surface temperatures that intensify climate change.

As opposed to welfare theorems like Pareto efficiency, which require benefits to be allocated not at the detriment of others, an equity principle calls for redistribution of the benefits from places of glut to places of need, as well as redistribution of cost to the responsible and/or capable. Climate equity, or climate justice, requires the consideration of this past cost. The principle requires those who have benefited in the past to compensate for the cost they have incurred.

The current international governance of climate change is centred on the Paris Agreement, which builds upon the UNFCCC as a treaty for international collaboration on addressing climate change. The treaty does this by asking country parties to independently communicate and commit to Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC), outlined in Article 4. This mechanism allows a country to set an individual contribution according to national circumstances. The implementation of NDCs is reviewed every five years in a Global Stocktake, the first of which concluded in 2023.

The differentiation of contributions among countries is to observe the CBDR-RC principle. Besides, developed countries are also asked to lead by pursuing “economy-wide emission reduction” and transferring resources such as finance, technology, and capacity building to developing countries through provisions in Articles 6, 9, and 10.

The voluntary nature of the pledge-and-review of the NDC mechanism makes it difficult to impose a top-down redistribution among countries, much less an equity-informed one. Countries are tasked with implementing climate solutions to achieve voluntary targets. Developing countries face the double challenge of achieving development under mounting constraints while being pressured to take on mitigation burdens equal to that of developing countries. Unfortunately, developed countries are not aiming proportionate to their fair share.

Carbon budget and the bathtub analogy

An equitable global climate effort involves the foundational problem of sharing the common atmospheric resource. To arrive there, we first need to understand the physical processes of global warming and how human interference has led to climate change.

The carbon cycle is one of many Earth processes that regulate the energy flows of the planet. The balance of carbon in the atmosphere, land, and ocean has sustained the energy throughput required for life to exist for millennia. This equilibrium is no longer stable as it has been disturbed by human activities through the burning of hydrocarbon fuels that release GHGs, the major one being carbon dioxide, often referred to simply as carbon. Humanity is a significant disturbance to the climate system due to the exceptionally large amount of GHGs released and the amount of global warming we have caused in a short period. The spike in GHG emissions can be primarily attributed to industrialisation.

Excessive GHGs in the atmosphere trap solar radiation, a process called radiative forcing, which heats the ocean surface, leading to evaporation. 50% of the atmospheric heat energy is stored in water vapour in the atmosphere. Without sufficient cooling, water vapour does not condense into rain. Water vapour stays in the atmosphere and feedback into further warming.

As human activities have historically emitted and continue to release GHGs into the atmosphere, the accumulation of carbon stock in the atmosphere has not been balanced by an adequate rate of long-term carbon sequestration, thereby storing energy (as heat) in the atmosphere. This, in turn, causes extreme climate responses, cascading further disruptions in natural and human systems. As climate feedback can be induced by past emissions over varying timeframes, it is therefore important to take into account historical and cumulative GHG emissions.

Fairly sharing the burden of solving global warming

As most of humanity is affected by climate change, solving the climate problem requires a collective effort. However, it would be grossly unfair to assume everyone is equally responsible, let alone equally capable.

It would be unfair to ask everyone to contribute the same amount, as some have used up more atmospheric resources in the past than others. Those struggling to make ends meet can barely allocate resources to emissions reduction and may need more of the carbon budget to achieve a more dignified life. Not to mention those who are affected by the ramifications of devastating climate impacts.

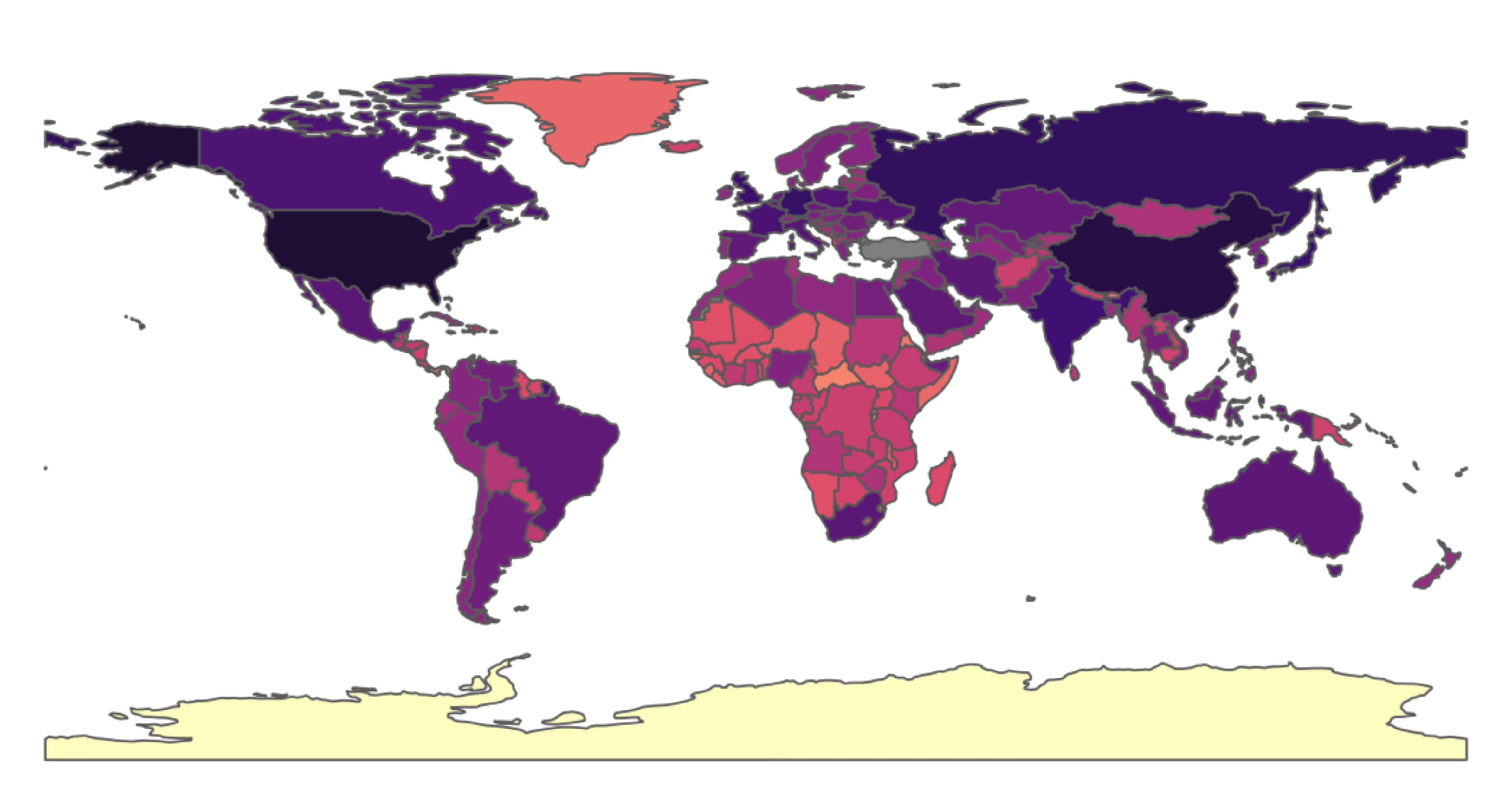

Differences in responsibility and capability worldwide are so stark that only 31 countries are responsible for half of the world’s cumulative emissions. Developed countries like the United States (USA) account for a quarter of cumulative GHG emissions in the world. Russia, China, and India have only recently risen to top emitters, although their per capita emissions remain low. If we measure capabilities by national affluence, using gross domestic product (GDP) per capita as a proxy, only ten countries have five times more capabilities than the world average.

This tells us two important things: first, in sharing the effort of solving the climate problem, an equitable burden-sharing regime is needed to allocate the burden of mitigating climate change fairly. Second, most developing countries are still in dire need of reaching levels of social well-being that are impossible without also improving material conditions, which warrant some levels of GHG emissions.

For fairness in a system that allocates burdens and benefits, one commonly refers to rules such as “polluters pay” and needs-based allocation. These rules recognise the equity obligations of those who have caused the problem and benefited most from doing so, even if unwittingly. Furthermore, with more capacity to clean up the mess, they need to assume responsibility.

A fair burden-sharing regime should function like a progressive tax system, where those with more responsibility for causing the problem and higher capabilities should contribute much more. It is no coincidence that high-responsibility and high-capability countries overlap most of the time, because GHG emissions of the past are correlated with the lopsided growth of the world economy and the grossly unequal development of their economic and financial capabilities.

These capabilities allow developed countries to experience accelerated technical change that makes their current economic decoupling from emissions possible.

Measuring fair shares of mitigation obligation

International climate treaties do not define the metrics of differentiated responsibility and capability. This has spawned many attempts to bring burden-sharing by CBDR-RC into practice.

Burden-sharing approaches differ in the principle of allocation. For example, some approaches that utilise the climate debt concept allocate emissions allowance according to per capita historical emissions. This approach allocates the least-responsible and most vulnerable countries with the most atmospheric resources or the right to emit. Most burden-sharing frameworks follow the “polluters pay” principle regardless of methods. The common measure of historical responsibility is cumulative GHG emissions, and the common measure of capability is the economic size of a country or average national income (GDP per capita).

Conceptualising differentiated burden-sharing and putting it into practice is equally challenging. The Paris Agreement provisioned that developed countries should “take the lead by undertaking economy-wide absolute emission reduction targets”. Developing countries are “encouraged to move over time towards economy-wide emission reduction”. In this, developing countries are given the space to pursue developmental priorities before climate goals, while developed countries ought to lead by either enacting deeper emission reduction or achieving targets earlier. How much should they outdistance the developing countries, and how ought the criteria of the differentiation be determined? How much each country should contribute to addressing climate change to be considered a fair contribution?

The Climate Equity Reference Project (CERP) developed a burden-sharing framework that takes into account both responsibility and capability in quantifying the countries’ fair shares to meet the required 1.5°C pathway. The approach allocates the burden as a share of the required global emission reduction to each country based on the country’s cumulative emissions and the obligated share of per capita national income.

Conclusion

At the current juncture, not only does the impact of unabated emissions rein in the development pathways for developing countries, but the deep inequalities and interdependence of our global economic system make it hard for them to develop sustainably alongside building climate resilience. Vulnerable individuals in developing countries can be further marginalised by national climate policies that are inequitably designed. Climate solutions designed in the name of market efficiency cannot deliver the fairness that the global climate effort needs, nor does it take into account the needs of the vulnerable in developing countries. Governments of developing countries should follow the equity principle in adopting and implementing climate solutions and avoid policies that can harm overall sustainable development goals.