Introduction

The “economy” is conceptualised in the popular imagination as a relatively autonomous realm of production and exchange of goods and services, operating with its own logic and principles of market efficiency, profit optimisation and perpetual growth. On the other hand, “households” carry the connotation of coresidency, where resources are organised and shared between household members underpinned by the logic of social reproduction (Harris 1981, 139).

The separation of the economy and households into two separate realms, grounded in two different sets of logic, has traces in the “disembeddedness” of the economy articulated by Karl Polanyi in The Great Transformation (Polanyi 2001). Polanyi argues that the economy, under laissez faire capitalism, has been severed from society, in which market forces of supply and demand reign supreme in regulating how resources (land, labour, capital) are allocated in the production and exchange process to generate profits (Dalton 1965, 25-27). However, this disembeddedness has not always been the case, as exemplified by traditional, pre-capitalist societies where their economies were more “embedded” in society, or in, what Polanyi calls, the logic of redistribution and reciprocity (Dalton 1965, 14, 27). Broader economic anthropology studies have also lent support to the argument that there are different ways of organising production and exchange that are more embedded in the everyday functioning of society (Malinowski 1922; Bohannan 1955; Mauss 1990).

Therefore, the importance of studying households for an analysis of the economy can be located within this economic anthropology paradigm, where the economy must serve the larger interests of society, or what is also known as the “substantive” definition of the economy (Dalton 1965, 15). A substantive understanding of the economy centres the restructuring of relationship between the economy and society, more than the increase in income or profit in a narrowly defined economic realm, as a pathway to progress.

Taking leaf from this discourse, I theorise households as an indispensable, but often neglected, feature of society, and offer three arguments on why it is important to foreground households in our understanding of the economy. These arguments pivot around the inseparability of production and social reproduction, gender exploitation in patriarchal capitalism and broader notions of households beyond the nuclear family. The conclusion draws together these arguments and discusses their significance.

Inseparability of production and social reproduction

Focusing on households in our analysis of the economy has the potential of making explicit the links between production and social reproduction, which have been artificially separated in the historically constituted process of capitalist development. Prior to the rise of industrial capitalism, households were the sites where home-based production took place, mainly to satisfy the subsistent needs of households (Davis 1983, 224-227). Exchange of household production happened under very restrictive circumstances, buttressed by non-monetary principles such as the reciprocal exchange of surplus production, or extraction of commodities by a centralised authority for the purposes of tribute payment or redistribution (Bohannan 1955; Dalton 1965; Mitchell 1998).

However, industrial capitalism shifted the centre of production from households to factories, while production activities that were non-tradeable but still crucial to the maintenance of workers remained within households (Davis 1983, 227-228). This has resulted not only in the separation of production from social reproduction, but also split the conception of value into exchange and use value, with the economy being viewed as a domain for hosting profitable, productive work, with exchange value, while households are viewed as spaces for non-profitable, social reproductive work that produces use value (Harris 1981, 142). The separation of production and social reproduction, with implications for our understanding of value and productivity in different spheres, is also incisively articulated by Davis (1983, 228):

“While home-manufactured goods were valuable primarily because they fulfilled basic family needs, the importance of factory-produced commodities resided overwhelmingly in their exchange value—in their ability to fulfil employers’ demands for profit. This revaluation of economic production revealed—beyond the physical separation of home and factory—a fundamental structural separation between the domestic home economy and the profit-oriented economy of capitalism. Since housework does not generate profit, domestic labour was naturally defined as an inferior form of work as compared to capitalist wage labour.”

Hence, the historically specific episode in the development of industrial capitalism has relegated households to the realm of use value, where all forms of activities that take place within households are conceived of as “domestic” activities, or worse, as “natural” activities, defined precisely by the absence of market transactions and exchange relations (Harris 1981, 142). It is in this sense that the onset of capitalism has rendered households and the activities residing within them invisible, not so much in terms of households not being identifiable as a domain of analysis, but more to their contributions being concealed from, and not recognised in the functioning of, the modern capitalist economy.

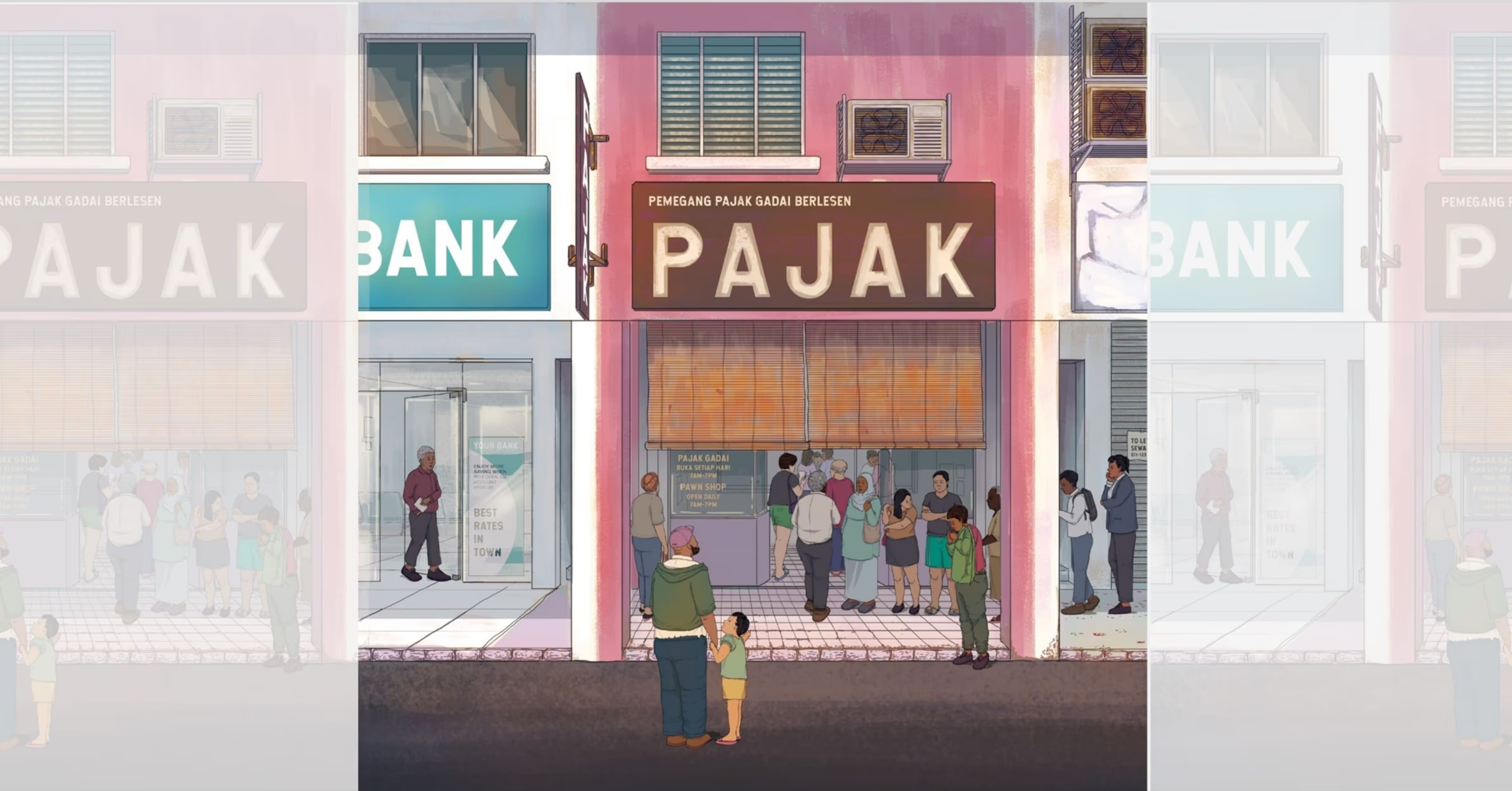

The transition from industrial capitalism to neoliberal capitalism has put an added strain on households as the state retreats from welfare provision and the private sector turns social reproductive activities into commodities (Fraser 2016). An increasing amount of activities in household production have been outsourced to the market as new sources of growth and profit e.g., food deliveries, laundry services, care services, cleaning services, but they are affordable only for the rich and affluent households (Jeffries 2018).

Nonetheless, the separation of production and social reproduction remains artificial because the newly commodified care sectors and affluent households rely on the exploitation of low-waged, feminised foreign domestic workers from poorer countries to take up these jobs (Bettio, Simonazzi, and Villa 2006; Williams 2012; Da Roit and Weicht 2013). The low remunerations underpinning these global care chains (Hochschild 2015) are usually unable to cover the social reproduction costs of these workers, as well as the care needs of their family members back home. In other words, the social reproductive work of households in poorer countries are effectively subsidising the productive activities and economies of richer countries.

The role of households in absorbing the social reproduction costs of production taking place in another geographical context is not just happening across borders, but also within the borders of countries as well. This is clearly highlighted in the anthropological work of Shah and Lerche (2020) in India, demonstrating how, at the site of origin, households participate through various forms of social reproductive activities e.g., subsistence farming, petty commodity production, small-scale animal husbandry, in enabling individuals to migrate to the site of production as seasonal migrant labour.

All the above underscore the importance of centring the intertwined relationship between—and ultimately inseparability of—social reproduction and production in our understanding of the economy, which can only be achieved if households are foregrounded as integral to economic life.

This particular way of approaching households and the economy also raises new questions on whether capitalism can continue to reproduce itself, under what conditions and at what or whose costs, all of which portend a more comprehensive analysis of the economy and the evolution of global capitalism.

Gender exploitation in patriarchal capitalism

The fictitious separation of production and social reproduction underlying mainstream conceptualisation of the economy has a very strong gender dimension as well, in which men dominate the former and women the latter. Consequently, looking at households not only draws attention to the invisibility of activities that take place within households, but also carries the possibility of unveiling women’s hidden work in the socially constructed private domestic space, leading to a more theoretically informed set of solutions in addressing gender inequalities in the economy and households.

The centrality of gender oppression in capitalist exploitation is manifested in contemporary times through social reproduction theory (Bhattacharya 2017), offering the view that such exploitation is derived from the processes of patriarchy interweaving with capitalism—or patriarchal capitalism—in producing distinct forms of exploitation of women’s work (Ferguson et al. 2016). At the same time, these exploitations are often obscured through notions of “marriage” and “love”, which characterise women’s work at home as “acts of love”—natural, affective and feminine (Federici 1975, 2-4).

The essentialising of women’s work in such a manner has become fodder for the exploitative practice of not recognising such activities as work and hence, not remunerating women for their domestic labour. The non-recognition and non-payment of women’s domestic labour lies at the heart of the International Feminist Collective’s critique of patriarchal capitalism and liberal feminism in the 1970s, led by autonomist feminists such as Silvia Federici, Mariarosa Dalla Costa, Selma James and Leopoldina Fortunati (Federici 2012, 92).

This movement culminated with the Wages for Housework campaign, a demand for a weekly wage paid to women by the government as a way of recognising their domestic labour as work and destroying the essentialising feature of housework as feminine (Dalla Costa and James 1975; Federici 1975). While wages for housework was ultimately not implemented, the campaign shifted the gaze and gender struggle away from male-dominated factories to female-dominated households. The historic campaign reinforces the importance of situating households in our analysis of the economy in order to put forward a more exact articulation of gender exploitation under different permutations of capitalism.

Against this historical backdrop, the unpacking of gender exploitation by studying households in the economy is particularly pertinent under neoliberal capitalism, where women have been marshalled by economic forces in an extensive way to join the labour market, often in the services sector (Fraser 2016). Despite participating in the economy, women still have to shoulder the bulk of responsibilities at home, given impetus by the essentialising aspects of patriarchal capitalism, resulting in what is called the “double burden” for women (Hochschild and Machung 2012).

Although the double burden is not new, as Black women have been facing it even from the onset of industrial capitalism (Davis 1983, 231), the scale and intensity of the double burden would have heightened under the contemporary crisis of care engendered by neoliberal capitalism. The low wages of women who participate in the economy means that they could not afford to procure care and domestic services from the market; and would have to resort to either reducing their leisure time (Stalker 2011), hiring even lower-paid (often migrant) domestic workers (Kofman and Raghuram 2015) or getting help from informal kinship networks (Stack 1975; Koch 2015), all of which are feminised processes affecting women disproportionately.

The devaluation of women’s work also extends to paid work, whether they take place in the formal economy, as evident in the low wages paid to workers in the feminised, commodified and competitive care sectors (Folbre 2006), or within households. On the latter, the anthropological work of Mies (1982) provides an illustration of how the mystification of work by housewives as “non-work” has kept women’s pay low and suppressed. Mies (1982) studied the lace industry in the villages of Naraspur in the West Godavari District in India, focusing on women who have been producing lace at home for the export market. The women internalise their wage exploitation by viewing their lace making as something that they do in their extra time to supplement their husband’s incomes. The ideology of the housewife, or what Mies (1982) calls “housewifisation”, compels the women of Naraspur to see their lace making as producing use value instead of exchange value, hindering them from bargaining for higher wages despite their contributions to capital accumulation and expansion of the lace industry.

Therefore, studying households is important for an analysis of the economy because it centres gender exploitation at the heart of capitalist development, and highlights the naturalising effects of women’s work in both the productive and social reproductive spheres, with repercussions for the adequacy of wages, availability of time, conditions of work and quality of occupations.

Broader notions of households beyond the nuclear family

Thus, the essentialising of women’s work has created a tautological reasoning, where the labour within households is devalued as women’s work, and women’s work, even when it takes place in the formal economy, is valued “in the shadow of the housewife” (Harris 1981, 151; Davis 1983, 238). This entire tautological edifice is built on, and sustained by, the myth of the nuclear family (married couple with children) being the ideal type of household for society (Harris 1982). In this sense, studying households, at least within a critical perspective, has the capacity of breaking this myth by featuring the multiple ways households interact with each other in their everyday life, as they navigate the demands of work in the formal economy and work at home.

Instead of being the ideal type, the nuclear family is a configuration of the household to serve a specific phase of capitalism (Dalla Costa and James 1975). The nuclear family household is normalised and concretised by administrative functions like census taking and policy targeting, which are foundational to state organisation and capitalist expansion (Harris 1981, 146; Shamsul 2001).

However, there are downsides to the construction of the nuclear family as the ideal type. First, it leads to inadequate understanding and theorising of households that deviate from the nuclear family (Harris 1982, 144). Second, it tends to skew towards men being chosen as household heads, simply for the fact that men are seen as the main participant in the formal economy (or breadwinners), again, assessed from the perspective of exchange value (Harris 1981, 146). Third, it does not emphasise the relationships between households, not only in terms of their interactions but also the “distribution of people” between households i.e., the changing composition of households (Harris 1982, 144).

Anthropological studies have shed light on how participation in kinship networks is fundamental as a mode of survival for low-income households and highlights the constantly changing household configurations among low-income communities. In this regard, Koch (2015)’s ethnographic study of welfare recipients living in a council estate in England is particularly illuminating. The study highlights how the welfare state constructs welfare recipients as “destitute individuals” (Koch 2015, 85, 92), with the conditions that they must declare additional incomes and additional household members, which could reduce their benefit amounts (Koch 2015, 90), contingent on the idea that these welfare recipients must be independent, standalone households to qualify for welfare. However, these requirements often conflict with the realities of welfare recipients, who would collaborate across households through informal support (monetary or otherwise) and accommodate additional persons in the household when the need arose.

Similarly, Stack (1975)’s anthropological work looks at the formation of kinship networks among low-income Black communities living in the ghetto in the United States. The study’s arguments are penetrating in the sense that it challenges the idea of the “unstable” poor families (assessed from the lens of the nuclear family), by demonstrating that despite the constantly changing configurations of households, the kinship networks formed were stable and durable. Interestingly, both Koch (2015) and Stack (1975) describe the kinship networks as matrifocal, suggesting that the determination of household heads, when considered from the perspective of use value, could lead to more women being identified as household heads.

Such critical, ground-up interrogation of households enables us to understand the diversity and richness of household types and inter-household relationships in supporting people’s participation in the economy. One could also think about the urbanisation processes accompanying economic growth, which would likely drive the formation of many young, singlemember and non-family households in the cities, and compel grandparents to migrate to urban centres to help with care work, the sum of which challenges the assumption of the nuclear family as the ideal type underpinning the economy. Furthermore, studying the relational character of households provokes a rethinking of how the economy could be configured differently to better support the collaborative nature of households, whether through the reduction of working time, flexible working hours and other policy measures that could enable workers to participate more fully in community life.

Conclusion

In this article, I have put forward three arguments on why the study of households is important for an analysis of the economy. First, the foregrounding of households provides an avenue for the reconciliation of production and social reproduction in our conceptualisation of the economy, which can only broaden our understanding of how the economy functions and evolves. Second, the focus on households centres gender issues in a more holistic way, locating gender exploitation at the intersection of production and social reproduction, which can lead to a more theoretically informed set of policy prescriptions. Third, the critical, ground-up interrogation of households provides more nuanced insights into inter-household dynamics that support household participation in the economy, as well as generate the empirical basis for how the economy can be configured to better support multiple household types beyond the autonomous, nuclear family. Although these three arguments are conceptually separated, they are fundamentally set off by the same processes found in patriarchal capitalism, and hence, should be understood as inextricably linked, and rooted in the same phenomenon.

There are also three ways in which these arguments, viewed as a whole, are significant. First, they amplify households not only in terms of their role in reproducing workers for the economy, but also in the larger sustenance of human life. This is perhaps most evident during the ongoing pandemic, where we have seen households being at the forefront of absorbing the shocks of the crisis through household production and inter-household exchanges, when other conventional economic spaces (e.g., retail centres, supermarkets) are closed. Second, they prompt a deeper reflection on the policy tools that are needed to address gender exploitation and the global care crisis, while offering explanations for why existing prescriptions that are confined to the economic realm would be gravely insufficient. Third, they provide a concrete articulation on what it means, in Polanyi’s terminology, to “reembed” the economy into society, or for the economy to serve the interest of society, through the lens of households.

To put it another way, the study of households for an analysis of the economy opens up new inquiries on, and provides insights into, how the personal—household production, domestic labour, and care work—is indeed, and in many ways, the political—global care crisis, welfare design, and the gendered economy.