Introduction

The government has introduced and implemented many interventions to improve housing access, quality, and affordability. Yet, many problems within the housing sector persist. In particular, housing overhang, vacant units, and abandoned housing projects reflect the systemic failures of Malaysia's Sell-then-build housing delivery system. Between January to September 2024, the Task Force on Sick and Abandoned Private Housing Projects (TFST), rehabilitated approximately 371 problematic and abandoned housing projects involving 46,139 private housing units, with a GDV of RM44.59b, with many others still awaiting intervention.

This article explains how Malaysia's Sell-then-Build system breeds structural inefficiencies and embeds perverse incentives for actors in the housing industry. The Government's recent announcement to institute a mandatory shift to the Build-then-Sell system is commendable and timely; this reform must be fully supported to improve house building practices in the country and ensure better quality housing for households.

The unequitable allocation of risks in housing development

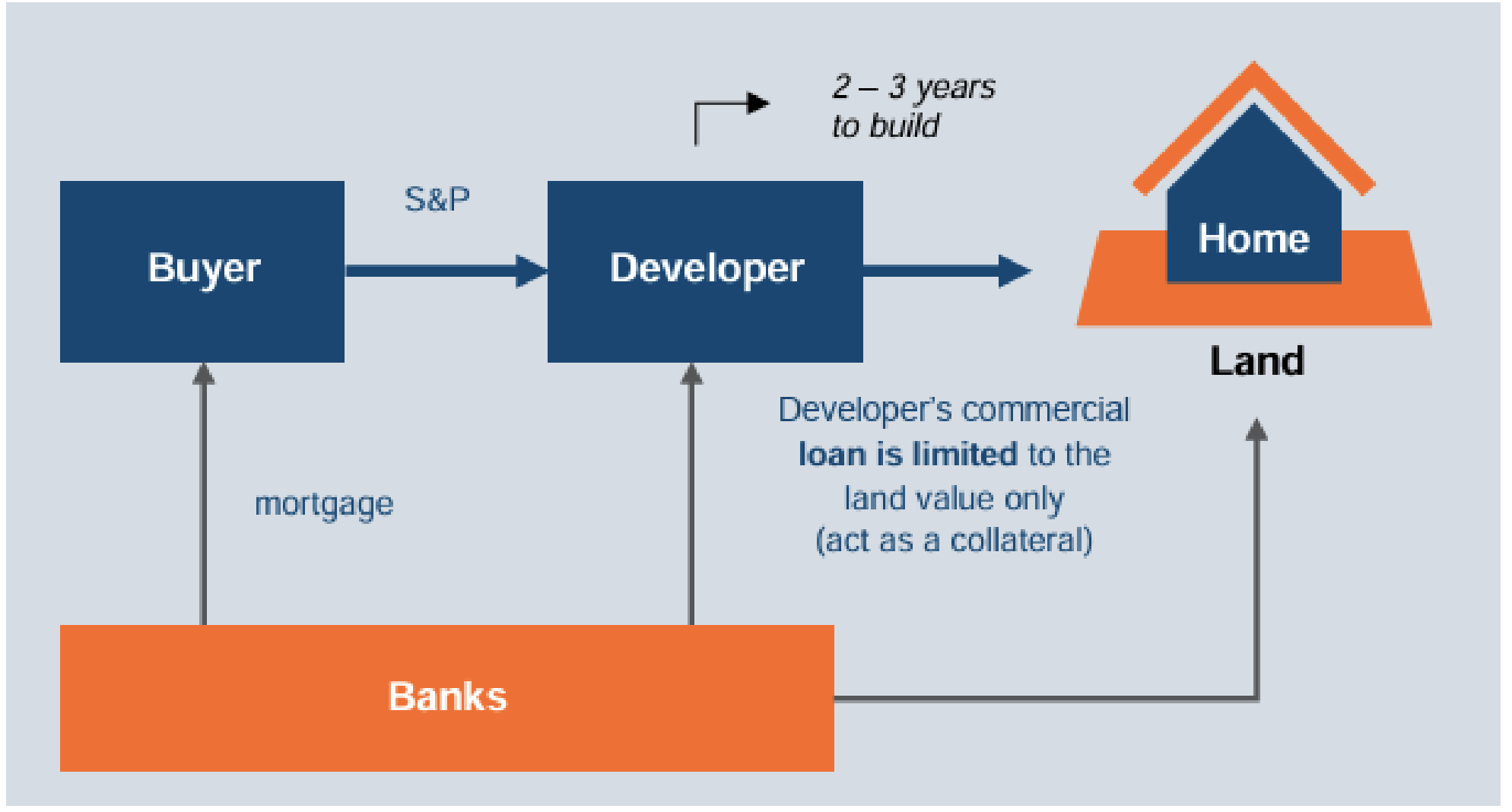

In Malaysia, individuals or families who want to own new homes are forced to buy houses before they are built through the Sell-then-Build (STB) system. In exchange for a house (which is promised to be delivered within the stipulated period), the purchaser agrees to provide full payment of the purchase price to the developer, which funds the construction of the project. These funds are usually secured through a loan agreement with a bank (i.e. mortgages), which is then disbursed in stages to the housing developer's Housing Development Account (HDA). In this system, the home purchaser essentially borrows money to attain their housing whilst providing working capital to developers to build these homes i.e. it is a form of conduit financing.

Under the STB system, housing developers and banks benefit by shifting the costs and risks of housing development to the house buyer. By linking consumer mortgages to the production of housing, our housing delivery system allows housing developers to gain access to essentially free financing to build houses as the financial costs and risks are primarily borne by the buyers. It also allows banks to subvert their role as the bearer and provider of capital, by circumventing the risk of investment into housing development projects and embedding guarantees within the system to capture the gains of housing development without the associated risks.

Build better housing: Realign the risks and rewards of housing development

At its core, the STB system (as practiced in Malaysia) is problematic as its risk allocation structure fundamentally creates perverse incentives for actors in housing development i.e. housing producers and financiers. The adage, 'having one's cake and eating it too', rings loudly and clearly in this arrangement, for both the housing developer and the banking system. Both profit from the system while avoiding the major financial, commercial, and construction risks of housing development projects. They can do so as the STB system allows them to shift these risks to the unknowing and unprotected home buyer.

In building houses, there is no incentive for housing developers to build faster or to modernise their construction methods; the STB system allows developers to lock in profits at the start of the project and affords them 2-3 years to deliver the units. Furthermore, housing developers are also not incentivized to deliver good quality housing as purchasers do not have the right to withdraw from the Sales and Purchase Agreement (SPA) even if their completed units do not follow the specifications outlined in the SPA. The risks of non-compliance and delays in construction are ultimately borne by the purchasers.

Similarly, banks face little to no consequences in recovering their capital when housing projects fail, gets delayed or abandoned. As a secured creditor, banks are prioritized and will be compensated in the event of insolvency and liquidation of the developer company. Additionally, mortgages attributed to the failed housing project, which were disbursed by banks to housing developers for the construction of the project and undertaken by the home buyer, are still due to be paid in full by the purchaser. In short, banks have no incentives to ensure the viability or completion of a housing development project as it retains its capital regardless of the outcome.

Way forward: Move to the Build-then-Sell system

It is time to place the risks of housing development rightfully to those who stand to benefit the most from it. The Government's move to enforce a mandatory shift to the Build-then-Sell system is a significant step in realigning the risk and rewards of housing development amongst actors within the industry. It is also a critical institutional pivot in relieving home buyers from the unequitable allocation of risks that they have been forced to undertake within the existing STB system. This move must be strongly supported by all parties who advocate for better housing for Malaysians.