Introduction

It is one thing to build homes, but quite another to ensure thathomes are decent to live in.In Malaysia today, we have regulations that govern howhomes are constructed, such as building codes and floorplans. Separately, we also have public and social housingprograms that operate at scale. But we do not have, at leastnot in any legally binding and enforceable way, a cleardefinition of what makes a home liveable, and the absence ofthis definition has consequences.

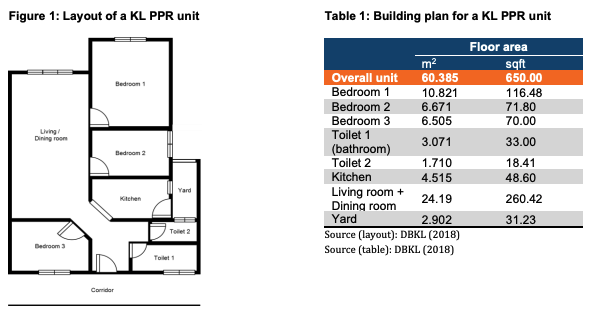

Consider the current state of housing policy. Developers areencouraged but not compelled to adhere to guidelines. TheConstruction Industry Standard (CIS) 26:20191, ourconstruction industry standard outlines the minimum dimensions and amenities for residential units. But it is a standard in name only, a benchmarkwithout legal bite. The Uniform Building By-Laws 19842, specify the absolute minimum instructural terms: a bedroom must be at least 6.5 square meters, a bathroom 1.5. Enough to fit abed, perhaps, but not enough to guarantee dignity.

The result is a quiet but persistent form of housing precarity. In the private rental market, tenantssign leases that are long on obligations, but short on protections. They find themselves payingmarket rates for rooms that might have no ventilation, unreliable plumbing, or shared access tobasic sanitation. In the public/social sector, a family of 6 or more squeezes into PPR units that aremore suited for a family of 3 or 4. The result of which are spaces too cramped for privacy, let alonethe simple act of studying for an exam.

It is not as if we lack shelter. What we lack is a national commitment to standards that enablepeople to live with dignity and to aspire beyond mere subsistence.

What Happens when Homes Fail?

Imagine being a single mother raising 4 children in a 650 square foot PPR unit with threebedrooms. At night, one of your children has to travel to a nearby room, sometimes outside thePPR3 to study, just because there is too much noise and disturbance in the home. There is nofunctioning exhaust in the bathroom, so the walls remain damp, and mold triggers your youngestdaughter’s asthma. You can report these to building management, but it takes a long time to getsthings done. You do not own this flat. And under current regulations, you have no recourse. Youhave to tolerate and adapt to these living conditions.

Now imagine being a student, new to the city, renting a room in a converted shop lot. Your “room”is a partitioned corner with makeshift walls and a shared toilet down the hallway. You spendRM700 a month for the ‘privilege’. You have no say over who your roommates are, the ‘guests’that they invite in, and the activities that other tenants do in your unit. You cannot focus, cannotrest, but cannot afford to leave as there are no affordable options elsewhere for you.

While these are mere isolated anecdotes, they are symptomatic of a system that treats housing ascommodity first and necessity second. In the absence of enforceable standards, the housingmarket is induced to behave like a race to the bottom where profits are prioritized, whileliveability is a secondary condition that is negotiated. We talk a great deal about housingaffordability. When adequacy is ignored, affordability becomes a misleading metric. A cheaphome that endangers health or erodes dignity is not a bargain, but a policy failure.

Other countries have space standards

There are no universal benchmarks for housing provision. Standards tend to reflect the specificsocial, economic and cultural context of individual countries. However, several countries haveclearly defined ‘space standards’ to ensure a basic level of comfort and dignity in living conditions.

‘Space standards’ refer to a set of guidelines that outline the minimum acceptable dimensions andfunctional features of a dwelling unit4. These may include measurements on minimum gross floorarea, ceiling height, room sizes and the number of bedrooms appropriate for the household size.These standards are important to ensure that a house is more than just a roof over someone’shead but also a comfortable living space that supports the well-being and dignity of its occupants,allowing them to lead a decent standard of living.

Having adequate space in a home is vital for carrying out daily activities such as rest, study,storage and social interaction i.e. spending time with family and friends. It is also important inensuring personal privacy and maintaining household harmony. Whereas, inadequate livingspace may negatively impact the well-being of occupants, affecting their physical andpsychological health. For children, the lack of suitable space to study can hinder their educationalperformance while limited privacy may further weaken their family ties over time.

In Malaysia, housing standards have largely concentrated on building and constructionspecifications for new dwellings. They do not provide a framework or guidelines to upgrade thequality of existing housing stock or define suitable occupancy levels to prevent conditions ofovercrowding.

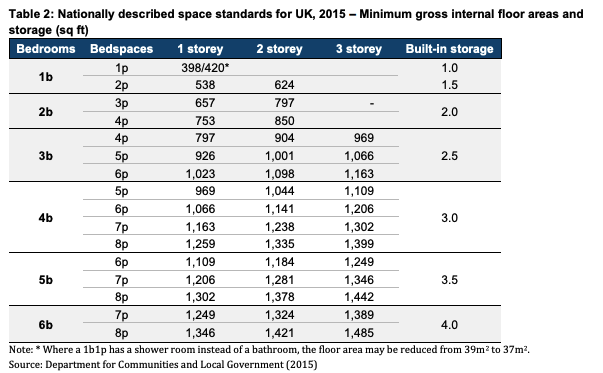

In contrast, several countries have adopted structured space standards that help ensure adequateand dignified living conditions. For example, the United Kingdom’s Nationally Described SpaceStandard outlines the minimum gross internal floor areas (GIFA) based on household size andnumber of bedrooms. A household of 4 to 6 persons is expected to have at least 3 bedrooms whilea 6-person household typically requires a unit exceeding 1,000 square feet. However, the contrastis stark when compared with Malaysia’s public housing experience, specifically the Projek Perumahan Rakyat (PPR). Many large households in PPR units live in conditions of severeovercrowding5 when measured against such international space benchmarks.

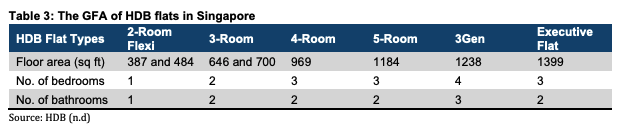

Similarly, Singapore has implemented a diversified public housing system through the Housingand Development Board (HDB), offering a range of unit sizes and layouts targeted for differenthousehold compositions. Over the decades, the design and size of HDB flats have evolved inresponse to rising living standards of Singapore citizens as well as to improve the quality of livingenvironments.

In 2017, the average household size of 3-room and 4-room HDB flats was 2.63 and 3.42respectively, considerably lower than the average household size of 4.5 in PPR units. This impliesthat HDB residents are less likely to experience overcrowding as compared to PPR residents,because HDB flats come in various types and GFAs, available for residents to select units basedon their needs and financial capacity.

Meanwhile, Malaysia’s social housing sector continues to rely on a ‘one-size fits all’ GFA approach,which fails to account for the diversity of household compositions. KRI’s study on social housing revealed that most social housing households consist of 3 to 6 persons, with household head smostly aged between 52 to 54 years6. Moreover, 1 in 10 households has at least one member withphysical disabilities. These demographic features highlight the need for more inclusive and responsive housing design that accommodates aging populations and supports accessibility needs.

Liveability compromised for cheaper rates

Another structural issue arising from poor housing standards is the prevalence of substandardunits in the rental market, particularly in urban areas. Landlords often refurbish existing unitsinto smaller partitions thus compromising basic living standards to offer rooms at slightly belowmarket rates. This happens because demand is high in dense, urban areas where affordable rentalsupply is limited. In extreme cases, so-called “coffin-sized” rooms are rented out for as low asRM300 in the Klang Valley7. Some students or working adults have no choice but to resort to thesecheaper options, resulting in them enduring a lack of space, poorly ventilated and inadequateliving conditions.

If adequate housing standards for shelter were in place and enforced, many of these substandardrental units or rooms would not be in the market in the first place. However, a key questionremains: is it possible to regulate opportunistic behaviour by landlords? Even when housingregulations exist, there is still no consensus on what constitutes an “acceptable standard”8. Whatsome landlords may consider adequate or “good enough” may not align with the ‘objectivestandards’ set by the state, building or healthcare professionals. This is a common challenge inless established markets such as ours.

However, this is not an issue for developed countries as they have adopted well-designedstandards, and they engage in continuous processes to improve and reconcile housing standardsfor both newly built and existing landlords and tenants. As a result, good quality standards areexplicit in the rental tenancy agreement between landlords and tenants in developed countries9.The local council or the agency in charge regulates and monitors both the rents and quality ofhouses in order to ensure that rent prices commensurate with the quality of homes provided.

Preventing building dilapidation through standards

Inadequate housing standards also contribute to long-term structural and financial challenges.When houses are built with substandard materials or poor designs, they tend to require morefrequent and costly maintenance. As a result, many low-cost housing projects face risks of physical deterioration driven by both substandard initial construction and limited funding for maintenance.

These conditions have led to recent proposals for urban renewal initiatives as a solution toaddress concerns over dilapidated and unsafe buildings. However, much of this deterioration could have been prevented through stronger construction standards and proper adherence tonational housing guidelines. Without clear and enforceable “acceptable standards” in place, urbanrenewal initiatives risk creating another similar vicious cycle of building deterioration.

Humanizing Housing

So how might Malaysia begin to close the gap between the homes that we build and the lives wewant these homes to support?

We could start with a National Housing Survey. This would be useful, not just to count units, butto assess conditions: space per occupant, adequacy of light and ventilation, access to clean waterand working sanitation. This is often complemented with a Housing Condition Survey to give theinstitutions a better description of the current state of housing conditions in the country. Withlimited information on the dynamics of housing demand and how housing markets haveresponded to them, the federal and state governments will not be able to plan and regulate thehousing sector effectively.

Next, we need a Rental Tenancy Act that protects tenants from unfair rental practices, includingdrastic rent hikes and substandard housing conditions. This should be a clear legal frameworkthat defines and protects minimum standards of habitability, particularly in the rental sector. Noone should have to live in a ‘coffin-room’, nor should have to plead for repairs.

We should also revisit our public housing design. A ‘one-size-fits-all’ flat may be efficient to build,but it is wholly inadequate for the diversity of family typologies that live in them. Largerhouseholds simply need larger units. Elderly residents need lifts that work all the time. Hence,building units of multiple GFAs catered to different household sizes would work best. This hasalso been recommended in an earlier KRI study10.

Finally, we must begin to think of housing as a platform for social mobility. A good home doesmore than shelter. It supports health, facilitates education, enables stable routines, and nurturesfamily life. In short, it creates the necessary conditions for human flourishing. If we want to builda fairer Malaysia, we must begin by building homes that are not merely habitable, but decent andliveable.