Introduction

In a high-rise apartment in Setapak, a young mother carriesgroceries and her child’s schoolbag down the corridor. Twodoors away, a man she has passed daily for years nods silentlyas he unlocks his gate. Across the floor, an elderly couplepeeks through their peephole. Inside each unit, familiesretreat into private routines. Screens glow, dinner is served,and the hum of the air conditioner mutes even the possibilityof hallway chatter.They are neighbours. But not quite a community.This scene plays out in high-rises across urban Malaysia.Lives stacked vertically, yet they remain socially distant. Formany, this disconnection is accepted as the price of modernliving. But it also raises deeper questions: Have our cities outgrown neighbourliness? Can the way we design space help us reconnect both physically andsocially?

Familiar Strangers

According to the Department of Statistics Malaysia, 6.5% of Malaysians report to have zero faceto-face interactions with their neighbours. For the remaining 93.5%, 41.4% interacted daily,41.5% weekly and 10.6% monthly.1

We are polite. We smile. We nod. But often, we stop short of allowing relationships to grow.

Robert Putnam’s work on social capital helps us understand why this matters. In Bowling Alone,Putnam distinguishes between bonding capital, which ties us to people like us, and bridgingcapital, which connects us across our differences – race, class, background, etc. In urban Malaysia,mechanisms to strengthen bonding exists: in suraus, ethnic enclaves and family circles. Butbridging capital, the kind that is formed through everyday interactions with people different fromyourself, is thinning

The erosion of neighbourly ties in dense environments is too a certain degree reinforced by theway space is designed. Shared corridors are narrow and transitional. Public areas are limited insize and function. Many social housing complexes were designed with cost-efficiency (and thenumber of units) in mind, as opposed to building spaces that facilitate community ties.

Culture matters, but so does design

It is tempting to explain this disconnection as cultural. Malaysians are polite, but private. We tendto jaga muka and respect each other’s space and privacy. That much is true. But culture doesn’texist in a vacuum. It is shaped and reinforced by the environment we inhabit. Even the mostreserved person is more likely to strike up a conversation on a shaded bench, than in a dark,sturdy lift. Cautious families are more likely to mingle if playgrounds and parks are designed toinvite lingering, casual observation and play

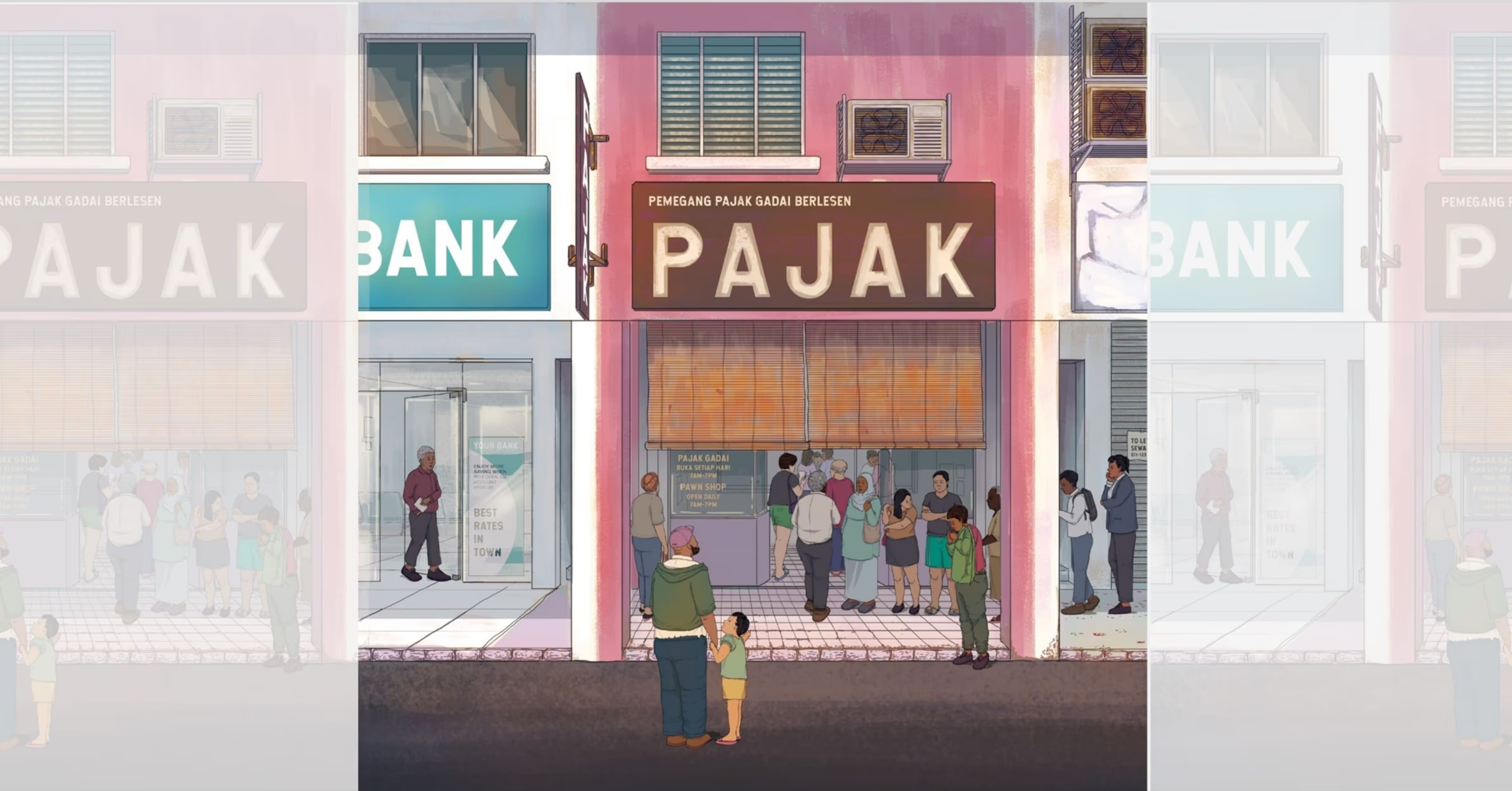

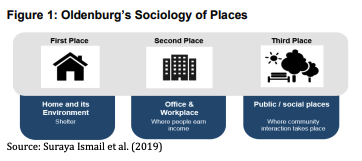

Urban sociologists like Ray Oldenburg have long emphasized the role of third places – the cafes,parks, suraus, that are neither home nor work, where people feel at ease, and slowly formcommunities around shared interests. 2 These spaces thrive on informality and accessibility

Jane Jacobs gives a similar set of arguments on how urban design fosters these encounters. Hercall for eyes on the street, while primarily driven by safety, is to a lesser degree about otherelements such as walkable blocks, mixed-age buildings, mixed-use neighbourhoods, and cornershops animate streets. These design elements bring people out regularly, seeding the lightencounters and loose connections that form the foundation of community.3

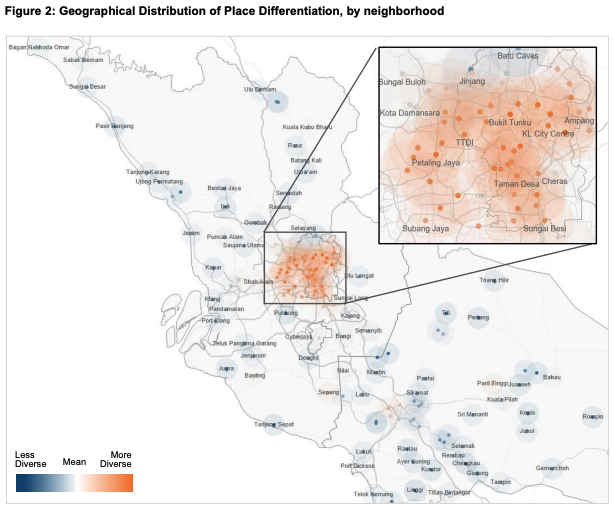

Malaysia has equivalents: kopitiams, pasar malam, suraus and public transport. But theirpresence is uneven. Denser, central areas like Bangsar or George Town offer greater access tosuch informal gathering points, while lower-income housing on city fringes often lack accessiblethird places within walking distance4 (see figure 2 below)

It would be simplistic to say that space alone determines social connection. Malaysians also livebusy lives. When time shrinks, neighbourly interaction may be the first to go. Add to this, the rise of gated developments, digital delivery, and social media and the picture becomes clearer: evenwhen we live near others, we rarely live with them.It is not that we dislike our neighbours. We just find it difficult to initiate and maintainrelationships.

Why should we care?

Some argue that deep connections with others are no longer necessary. Afterall, isn’t the familyWhatsApp group enough? Isn’t safety better handled by security guards and CCTVs?

Evidence suggests that this is more nuanced. Research shows that people who regularly greetneighbours, even casually, report higher levels of life satisfaction, wellbeing, and trust. A recentGallup study in the US found that happiness increased with each neighbour greeted, up to aboutsix neighbours.5 In Malaysia, studies among older adults show that robust social networks,including ties with neighbours, correlate with better memory, lower loneliness and greaterresilience.6

The benefits aren’t just individual. Neighbourhoods with strong bridging capital tend to feel saferand be more responsive. Residents are more likely to watch out for one another, to organizecollectively and respond better to crises. This is the very premise behind Malaysia’s RukunTetangga programme with over 8,500 active community units today

When neighbourliness decays, so does the social glue that makes daily life manageable.

The role of Policy and Design

So what can be done?

We need to stop treating urban design as background infrastructure. To be fair, many of the rightideas – benches, parks, community halls – already appear in our planning documents. But if goodintentions were enough, we wouldn’t be asking why so many shared spaces remain under or misused.

The problem isn’t always with what we plan. It’s how we plan and who we plan with. This is wherehuman-centered design becomes essential. As Don Norman puts it in The Design (Psychology) ofEveryday Things7, good design isn’t just about form or function. It’s about ‘affordances’. A benchinvites sitting only if its shaded, clean and positioned where people want to pause. A playgroundsupports communities only when people feel safe, welcome and included. A lack of ‘affordances’is when projects prioritise ticking the box for ‘seating areas,’ only for benches to be placed in anunshaded or dead space. The amenity exists, but the affordance fails.

We don’t need more features. We need to design with people, not just for them. Community inputcan no longer be just a checkbox at the end of the process. It must shape the process itself,informing how we sequence public-private space, when amenities are accessible, and whetherdesigns reflect actual routines. This shift from infrastructure to lived experience is where the realwork begins.

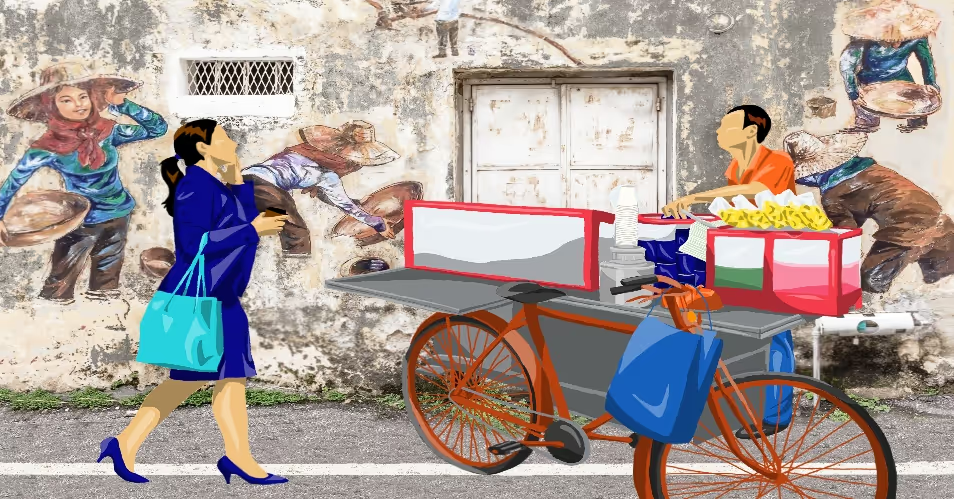

Think City’s pilot programmes, for example show how modest spatial changes – benches, murals,reconnected sidewalks, have measurable effects on foot traffic and social engagement.8 This is theessence of deliberate friction engineering: designing public spaces to create the conditions whereeveryday encounters become part of the spatial script. We need more inclusive environments iswhere individual contact and interactions become more probable.

Still, even the best-designed spaces won’t work without a change in social norms. Jane Jacobswarned against replacing local everyday acts of care and informal watchfulness with impersonal,top-down planning regimes. Because she observed that those informal systems tend to erode thevery social fabric they intend to protect. What we lose then is neighbourliness, the spontaneousoffer to help, the sense that we are each other’s first responders. Bringing that back doesn’t meanerasing privacy or imposing forced communities. It means recognizing that a city full of politestrangers is more of a choice. And like most social choices, it can be re-learned.

Conclusion

In policy, it is relatively easier to ask what works. A harder, better question is: what enables theconditions for good things to happen, even when we can’t predict them? We cannot plan everyfriendship, or neighbourly gesture. But we can shape spaces where they’re more likely to emerge.And in a time where disconnection is becoming the norm, this might be one of the quietest, yet most meaningful investments we can make.

.avif)